Firdose Moonda

This did not start on the eve of South Africa's World Cup squad announcement. It did not start at the IPL, when AB de Villiers is supposed to have approached Faf du Plessis with the suggestion of returning to the national side. It did not start with the fallout after the Champions Trophy two years ago, when de Villiers reluctantly let go of the ODI captaincy after du Plessis emerged as a better captaincy option, or even when he took a year-long sabbatical from Test cricket that year. This started seven years ago, in the UK.

In Taunton, hours after Mark Boucher suffered the eye injury that ended his career and without consultation with the selectors or anyone else in an administrative capacity back home, the South Africa team camp announced that de Villiers would keep wicket. This seemed a reasonable response to an emergency situation; also South Africa were fortunate that they had someone with de Villiers' varied skill set to call on. But it was a rushed call and its repercussions are still being felt.

ALSO READ: AB de Villiers sought World Cup recall, SA team management said no

The two main learnings that emerged from that decision were about the presence and power of a clique of senior players - which Herschelle Gibbs identified in a biography no one took seriously - and a disregard for the importance of transformation. Thami Tsolekile had been contracted as Boucher's successor in the lead-up to the tour and arrived eventually, but only to carry drinks. We can analyse the statistical merit of de Villiers over Tsolekile (and it will be a no-contest in de Villiers' favour) but we also have to look at the bigger picture. In the years after that, South African cricket was forced by its administrators to adhere to targets, most notably in a World Cup semi-final (which affected de Villiers' deeply) as well as by the country's government, which could have been avoided had the need to change been embraced earlier.

Ultimately, both those events contributed to how de Villiers' situation with the national team turned out in the years that followed.

Some days he wanted to be the next Adam Gilchrist - and he had the ability to be that and more. On others, a chronic back problem prevented him from crouching behind the stumps. Between 2012 and late 2015, when Quinton de Kock took a firm grip on the gloves, de Villiers swayed between wanting to play the dual role of wicketkeeper and key batsman to complaining that he was overburdened and would contemplate early retirement (a story that broke during the Boxing Day Test against England in December 2015). When de Villiers did both jobs, he thrived. He averaged 57.41 when keeping wicket, compared to 50.66 overall. That he could do it was never in doubt; whether he wanted to, whether he felt he needed to, or was forced to, is.

Then, there were some days he wanted to captain the side, while on others he was happy being led. De Villiers first threw his unequivocal support behind Hashim Amla when Amla was made Test captain following Graeme Smith's retirement, and later said in an interview that he had wanted the job. When Amla stepped down a year and a half later and de Villiers was made captain, injury prevented him from leading at first but then he willingly took that sabbatical from Test cricket, which meant he never served as the official, permanently appointed captain. But to his credit, when he saw how du Plessis led the team in Australia in late 2016, he stepped aside, though his desire to be part of a senior group never dimmed.

Eventually, there were some days when de Villiers wanted to play and others when he didn't. Like many players, when he started a family, de Villiers wanted more time off, which was understandable. He also wanted more money, so the IPL was an obvious choice. But then he used some of his rest period to dabble in the CPL while still playing for South Africa in 2016, which sent confusing messages about where his priorities lay.

ALSO READ: 'Decision based on principle; had to be fair to the team' - CSA selector on turning down de Villiers

Playing international sport at the highest level for more than ten years is tough and de Villiers said so many times. What he never explained was why he found it so much easier to travel to T20 leagues, leaving his young family at home. For that answer, we need to turn to the 2015 World Cup semi-final, where de Villiers was forced to pick a half-fit Vernon Philander in his XI. Of all the players who were let down that day, de Villiers seemed to take it the hardest. That was the World Cup he thought South Africa would win, and he was the one to lead them there.

After that incident, de Villiers picked and chose more regularly. After headline-grabbing his way through the England Tests at home in the 2015-16 summer, he opted out of the 2017 Test series against New Zealand and England, which South Africa lost. He came back for a home series against India in 2017-18, and then was the major contributor to a victory in a Test series over Australia, South Africa's first at home. They may never have achieved that if not for de Villiers.

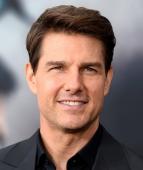

Some days de Villers wanted to lead, other days he was happy to be led AFP

The combination of frustration with de Villiers for choosing when he wanted to play, and fascination at his ability to justify his choices by performing when he did play became confusing. Should South Africa be angry with him for being selective? Grateful to him for turning up when he did? Accommodating to his needs?

It's difficult to know the right answer because in the middle of all this CSA have also been putting out other fires. The combination of the country's frail economy and the pressures of their transformation targets took its toll on other players, and a Kolpak exodus saw them lose men who could also be in the World Cup squad today.

One of them, Kyle Abbott, walked away, having just established a regular place in the squad. He was at the Hampshire Bowl to greet them before their match against India this week, on the same day Dale Steyn was ruled out of the tournament. Abbott laughed when jokes were made about whether he could be called up (he can't) but these things are not so funny anymore. South African cricket can't afford more crises, especially in the face of a T20 competition that has not quite set the world alight, and financial losses that are erasing vast amounts of their cash reserves. On the whole, confidence in the way CSA runs the game is at all-time low, and de Villiers was one of the people who felt that earliest.

ALSO WATCH: AB de Villiers: country v club (2016)

Considering that the South African Cricketers' Association is taking CSA to court over its decision to restructure the domestic system, de Villiers is not the only player with concerns, but he is one of the few who can do something about it.

In May 2018, he took the most drastic route he could and retired, saying so via an Instagram video. He also revealed that the World Cup was no longer a burning ambition, but the whispers that he still wanted the trophy never went away.

In October last year, when the first rumours that de Villiers was considering a comeback surfaced, he quashed them. "That is not true," de Villiers replied to a message I sent asking him if the World Cup was in his sights. He reiterated that shortly after, when preparing for South Africa's Mzansi Super League. "There is no comeback. I'm very, very happy with where I'm at in my life. I don't want to confuse anybody, especially not the [Proteas] team. It will be very selfish and arrogant of me to throw statements around that I'm keen to play a World Cup."

So de Villiers knew, more than six months before the World Cup, that changing his mind would be disruptive. But still, he could not resist.

Now there is disruption when the team is at its lowest, one defeat away from an almost certain early exit from the tournament, one senior bowler on the plane home, one junior bowler still nursing injury, and now with one major sideshow on their hands that could lead to a complete unravelling.

In some ways, you can't blame de Villiers for wanting to be involved, especially given the state of the current side. But you can only wonder how he managed to misread the team dynamic so spectacularly that he thought the door was still open for him. In the end, his numbers will ensure he remains a cricketing great. But his legacy will be defined not only by his excellence but also his indecisiveness. It's worth remembering that both of those were a long time in the making.

Torrent Invites! Buy, Trade, Sell Or Find Free Invites, For EVERY Private Tracker! HDBits.org, BTN, PTP, MTV, Empornium, Orpheus, Bibliotik, RED, IPT, TL, PHD etc!

Results 1 to 1 of 1

-

06-07-2019 #1Be A Man Touch The Sky

- Reputation Points

- 431433

- Reputation Power

- 100

- Join Date

- Mar 2018

- Posts

- 24,214

- Time Online

- 246 d 9 h 20 m

- Avg. Time Online

- 2 h 40 m

- Mentioned

- 2351 Post(s)

- Quoted

- 452 Post(s)

- Liked

- 5104 times

- Feedbacks

- 521 (100%)

Did AB de Villiers want to have his cake and eat it too?

Sweet Dream Nightmare Come Together

We are come from different Worlds

Who Will Really Care !!

Day Went Night Comes

Earth face this

untill the judgement day comes forever

People Here People There

Does Change The Clock

We Want To Be Damn Happy

Which Is Really the fact of this clock

= > NIL

How To Add Feedback Tutorial

TorrentInvites.org Forum Rules

How To Make Ratio Proof, Speedtest Proof or Seedbox Proof

LinkBack URL

LinkBack URL About LinkBacks

About LinkBacks

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote