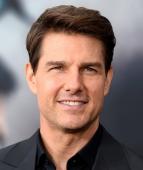

'Yes, I was troubled, but I was in charge and should have done more' Getty Images

Shahid Afridi's autobiography is not short of revelations, though few are as compelling as his role in the uncovering of the spot-fixing scandal of 2010. Afridi was briefly Pakistan's captain in all three formats that summer - he famously stepped down from the Test captaincy after only one Test, a defeat to Australia at Lord's.

But he had led the side in the Asia Cup in Sri Lanka and then the World T20 in the Caribbean leading into that English summer. And it was in Sri Lanka that he first discovered something crooked was afoot, when Mazhar Majeed, the player agent at the centre of the scandal, had to have his phone fixed after his son dropped it in the sea. Versions of this story, and Afridi's role in uncovering the corruption, have long been the subject of speculation in Pakistan and in Game Changer he confirms his involvement.

The following is an excerpt from the book in which Afridi opens up on his role, and alleges that a management wracked by apathy did nothing to stop it. It has been edited for brevity.

It was in this spirit that I got hold of the original evidence in the corruption racket: phone messages that would eventually come into play against the players involved in the spot-fixing controversy. But when I took that evidence to the team management, what happened next doesn't inspire much confidence in those tasked with managing and running the affairs of Pakistan's national cricket team.

Here's my account: I was in Sri Lanka on a tour when the text messages of Mazhar Majeed - Salman Butt's 'agent and manager', who was also prosecuted - reached me, in transcript form. It is pure coincidence how I got hold of them. And it's got something to do with a kid, a beach and a repairman.

See, before the Sri Lanka tour, Majeed and his family had joined the cricket team during the championship. At one of the Sri Lankan beaches, Majeed's young son dropped his father's mobile phone in the water and it stopped working. When Majeed went back to England, he took his phone for repair to a mobile fix-it. The phone stayed at the shop for days. In a random coincidence, the shop owner turned out to be a friend of a friend of mine (this may sound like too much of a coincidence but the Pakistani community in England is quite closely connected). While fixing the phone, the shop-owner, who was asked to retrieve the messages, came across Majeed's messages to the players of the Pakistan team. Though he shouldn't have seen what he did, it was that leak from him to my friend and a few others (whom I won't name) that looped me in on the scam. Soon, word got around that something strange was happening with the cricket team. It was that leak which probably tipped off the reporting team from News of the World as well. It was sheer coincidence: a Pakistani repairman in London who couldn't keep his eyes and mouth shut about a broken cellphone from Sri Lanka. But I'm not surprised: when God has to execute justice, it happens in the most unexpected ways.

Mohammad Amir, Salman Butt and Mohammad Asif look on Getty Images

When I received those messages back in Sri Lanka, I showed them to Waqar Younis, then coach of the team. Unfortunately, he didn't escalate the matter and take it upstairs. Both Waqar and I thought it was something that would go away, something that wasn't as bad as it looked, just a dodgy conversation between the players and Majeed, at worst. But the messages weren't harmless banter - they were part of something larger, which the world would soon discover.

The rumour mill started churning. During the World T20 that year in the West Indies, Abdul Razzaq, one of our finest players in the shorter formats of the game and an old, solid hand in the team, told me in confidence that Salman, [Mohammad] Amir and [Mohammad] Asif 'weren't up to any good'. I shrugged off his comment. I told him he was imagining things, secretly hoping that their shady behaviour was just a sign of their youth and inexperience. I never told him about the messages I'd received from London,which were all the more damning, considering that a third-party player like Razzaq with a tendency to refrain from locker-room politics was of the same opinion: something wasn't right with Salman and the lads.

However, during that infamous England tour in the summer of 2010, before all hell broke loose with the News of the World sting of the spot-fixing scandal, I saw Mazhar Majeed and his cohorts make a re-entrance, lurking around and hanging out with the soon-to- be-accused players. For me, it was time to sound the alarm. That's when I decided to take up the issue officially with the team manager, Yawar Saeed. I put in a formal request that Mazhar Majeed should be distanced from the players, physically, and that no one in the team should associate with him even on a personal level. I had my own reputation at stake as well - I was the captain of the T20 side - and feared that any controversy would harm the performance of my squad.

When Saeed didn't take action, I showed him the text messages - I'd printed them out on paper. After going through them, Saeed, taken aback, eventually came up with a dismal response: 'What can we do about this, son? Not much. Not much.'

Time stood still for me as Saeed went into denial. I couldn't believe what I was hearing from such a senior official. 'Not much'? How could we do this to the team, to the country, to our millions of fans across the world? I didn't want to believe what he told me.

Disappointed, I didn't respond or protest much. But I kept the printout with me. Saeed didn't even bother asking for a copy of it. The next day, at a warm-up game in Northampton, Mazhar Majeed and his sidekicks were again hovering around the dressing room. So I approached Yawar Saeed once more and suggested that these guys shouldn't be seen anywhere near the team, as they didn't have the best of reputations.

By now, the exchanges between Majeed and the players via text messages had leaked out to others. Those in the Pakistani and the larger cricketing community knew that something was up. This is probably the same period when the News of the World executed their sting operation.

I had done my own due diligence on Mazhar Majeed and his posse by then. Through my friends and connections in England, I'd come to know that these guys were trouble. Thus, I wasn't just making these suggestions to the management of the Pakistan team based on second-hand SMS messages, or being a paranoid conspiracy theorist. I had it on good authority that these guys, who were officially engaged in conversations with Pakistani cricketers, were indeed not up to any good. So yes, I was building a case against Salman, Amir and Asif - one that could be dealt with internally.

However, the Pakistan team management continued to be in denial and said that nothing could be done about it. Frankly, I don't think the management gave a damn. It still was nobody's problem; that's why nobody wanted to tackle it or go to bat for it. Typical obfuscation and delay tactics; the Pakistani management's head was in the sand. Maybe the management was scared of the consequences. Maybe they were invested in these players as their favourites and future captains. Or maybe they didn't have any respect for their country or the game. I really can't say.

So there I was, on that cursed tour, playing match after match, with a rough idea that something was seriously wrong, knowing that the management wasn't really interested in listening to me. I started going insane, really. We played two T20s against Australia and won both. That provided some relief,of course. Then we started the first Test, which we lost as we didn't - couldn't, wouldn't - perform.

Shahid Afridi and Mohammad Amir watch their team self destruct from the Lord's balcony AFP

You see, doubt is our greatest enemy. Doubts had started setting in a few weeks ago. I remember I was in the dressing room in Dambulla, for the Asia Cup, playing against Sri Lanka, when Salman Butt got out in the second over. Abdul Razzaq warned me at that very moment that something was up. I brushed him aside and said that we all got paid enough as match fees. He just gave me a strange look and told me to watch out. In that game, I went on to score a century and forgot about his comment.

But when I came to England, I wasn't over it, clearly. I had signalled to the boys to stay away from Majeed and the likes. I had tried to talk to the coach and the management. Then the first Test began. Nothing changed. I could still see them lurking around the players and being part of the dressing room too.

In that first Test, at Lord's, I started doubting the whole project. What was wrong with Pakistan cricket? What was wrong with all of us?

That's when I decided to put an end to it, in my own way. In the middle of the match, around the fourth day, I told Salman Butt that he could take over.

I remember exactly when I made the decision. We were at 220 for 6. Marcus North was bowling. I swept and was taken in the deep. When the ball was in the air, I had taken my decision. I was done with all of this.

Yes, I shouldn't have quit my team. Yes, I should have played the second Test and not gone home. Yes, I was troubled, but I was in charge and should have done more. Much more.

So, I retired from Test cricket. Perhaps prematurely, but I had lost faith in the whole set-up, especially because the team management wasn't proactively investigating what was happening and instead letting the entire thing slide. I was angry and frustrated with everyone, including myself. That's why I didn't wrap up the Test series against Australia and decided to head back home to be with my family instead.

Yes. For the record, I gave up. I quit.

Reprinted with permission from the book Game Changer by Shahid Afridi and Wajahat S. Khan, published by Harper Sport, an imprint of HarperCollins India.

Torrent Invites! Buy, Trade, Sell Or Find Free Invites, For EVERY Private Tracker! HDBits.org, BTN, PTP, MTV, Empornium, Orpheus, Bibliotik, RED, IPT, TL, PHD etc!

Results 1 to 1 of 1

-

05-05-2019 #1Be A Man Touch The Sky

- Reputation Points

- 431433

- Reputation Power

- 100

- Join Date

- Mar 2018

- Posts

- 24,214

- Time Online

- 246 d 9 h 20 m

- Avg. Time Online

- 2 h 40 m

- Mentioned

- 2351 Post(s)

- Quoted

- 452 Post(s)

- Liked

- 5104 times

- Feedbacks

- 521 (100%)

A kid, a beach and a repairman: How Shahid Afridi helped unearth the 2010 spot-fix

Sweet Dream Nightmare Come Together

We are come from different Worlds

Who Will Really Care !!

Day Went Night Comes

Earth face this

untill the judgement day comes forever

People Here People There

Does Change The Clock

We Want To Be Damn Happy

Which Is Really the fact of this clock

= > NIL

How To Add Feedback Tutorial

TorrentInvites.org Forum Rules

How To Make Ratio Proof, Speedtest Proof or Seedbox Proof

LinkBack URL

LinkBack URL About LinkBacks

About LinkBacks

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote