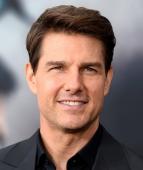

Immy to the max: we'll miss those celebrations, won't we? Getty Images

Osman Samiuddin

Senior editor,

Imran Tahir is never not feeling it but right now he is really feeling it. He's feeling it so deep that he almost doesn't understand that around him his side is falling apart. He's not even sensing that, right now, he's the one keeping them together.

Kagiso Rabada and Lungi Ngidi have already let slip the initiative. The fielding is already sluggish and it will soon be falling apart. Not Tahir. This is Lord's, the home of his game. He is here representing his home against his old home. It's one of the last times he will be on such a big stage. No, Tahir doesn't ever need a reason to be feeling it, but he's so alive right now, he has life enough to populate a planet. There's real danger the Tahir parody could become real.

He has almost taken a spectacular catch in the outfield, has two wickets, the second of which is off a breathtaking return catch. Each ball is drama. Everywhere you look is Tahir, party on top of his head, piety on the bottom of his face. Quinton de Kock drops an edge and Tahir crumples to the ground, like he'd been held up all this time by a clothespin. He's almost in a foetal position. He's up again in no time.

Tahir's standout numbers

58 Number of matches he took to get to 100 ODI wickets - the fastest South Africa bowler and eighth fastest overall to achieve this milestone. He was also the joint-quickest South Africa bowler to 150 wickets, with Allan Donald.

18.48 Tahir's bowling average in South Africa's ODI wins - the best among 21 South Africa bowlers who have taken at least 50 wickets in wins. Donald is next best, with 19.05. Tahir's 78.5% career wickets in wins is also the highest percentage of wickets taken in wins by a South Africa bowler.

5 Four-wicket hauls (or better) by Tahir in World Cups. The only other bowler to take more such hauls is Mitchell Starc. Tahir's 39 wickets in World Cups are also the most by any South Africa bowler.

7 for 45 Tahir's figures in a match against West Indies in 2016 are the best by a South Africa bowler in ODIs. He is the only South African to have take seven in a match in the format.

146 Number of wickets Tahir has taken in ODIs after turning 35. No other bowler has 100 wickets in the format after that age. Muttiah Muralitharan is second on this list with 87 wickets.

Now the next over and a flipper almost scuttles through. Tahir is down on one knee, in anguish and disbelief that all the powers that could be - God, karma, science, Mohammad Hafeez (the batsman) - have decided to not award this ball a wicket. Two balls later he's showing us that just as the colour of his passport hasn't changed, neither has that of his soul. This one's a googly. This one's a driftin' and griftin' and the batsman's a sweepin', and this is out. So plumb that Tahir - channelling Shahid Afridi - is not even bothering to ask his captain for a review. He has told the umpire, though even that's just following procedure - what he's really doing is telling the umpire he has no business being out there if he can't see that's out. As an afterthought, his captain does ask for the review.

Ball-tracking says no. Ball-tracking says ball bouncing over. The walls of the world are tumbling in on Tahir, who is doing what any man in this situation will do: he is chucking his sweater down in disgust. Then he is picking it up. Then he is walking off. Then he is bowling one more over. The purpose of this over is not clear, other than, at the end of it, to frame Tahir looking so defeated that Willy Loman seems a winner next to him. His team-mates are not sure how to be around this, but they've seen it so many times. Familiarity is this scene's ice-breaker.

This is from Tahir's third-last game for South Africa. Now we are coming up to his last. South Africa are long out of this tournament but just try and picture Tahir not feeling it.

Go ahead. Try.

***

Ish Sodhi says that if ever there was a WhatsApp group for the world's leggies, Imran Tahir would be its president. That's not just out of deference, because Tahir would be the oldest in such a group, it's also an acknowledgment that Tahir is, in some modest way, the father of modern white-ball leggies.

When he did finally arrive on the international scene, just before the 2011 World Cup, it's fair to say limited-overs legspin had been hiding for a while. It had gone past novelty - Mushtaq Ahmed and Shane Warne had been at the centre of World Cup wins long ago. But in the ten years before Tahir's debut, only five legspinners had more than 50 ODI wickets. Shahid Afridi was far and away the most prominent (219 wickets), then Brad Hogg (153), then daylight, and then Upul Chandana (73), who was a borderline allrounder and Anil Kumble (63), who played his last ODI in 2007. Sachin Tendulkar is the fifth, and that's all you need to know. Since then - less than a decade - there are already ten legspinners who have at least 50 wickets, and no spinner of any kind has more than Tahir's 172 wickets in this period.

At that 2011 World Cup, Tahir was one of eight legspinners for eight teams out of 14 (not counting either Steven Smith or Cameron White). One of them - Adil Rashid - didn't play a single game. At this year's tournament there are nine legspinners in just ten teams; only two teams don't have one.

Now nobody's saying Tahir has gone around planting seeds everywhere he has played. He has not been setting up legspin academies around the world, even though it is true that there are few young legspinners who haven't been given time by Tahir at some point. T20 has blown up and there's a causal relationship between that and the increase in leggies. But Tahir has left an unmissable footprint on the genre. Sodhi was asked what one trait he would pinch if he could from his fellow legspinners, and he chose Tahir's enthusiasm, rather than a specific skill.

But that's probably because almost everything we see now in legspin we saw first in Tahir. The flatter, quicker trajectories; not fretting about not having a big legbreak; turning the googly into a stock ball and not some mystery variation. It was this last that separated him from, say, Kumble, in whom otherwise you could also see this modern template.

Tahir had a googly and it was a great one - already in the past tense, see - and so why not use it as often as possible? Two, three, four times an over if necessary. He had a couple of variations on it, a little like the man whose help he sought to better it: Abdul Qadir, who also wasn't shy of putting it out there.

Nowadays the format has swung so far away from bowlers that it somehow feels revolutionary when bowling sides actively attempt to take wickets in the middle overs. But Tahir has been taking wickets in those middle overs all his career. And all his career means he has been taking wickets through whatever sets of fielding restrictions there have been in those middle overs: five fielders out, both bowling and batting Powerplays, no batting Powerplay, four fielders out, batsmen not taking risks, batsmen taking risks.

One hundred and thirty-three wickets (of his 172 overall) came in those middle overs; that's how good he has been. The only spinners with a better strike rate in those overs (with at least 50 wickets since Tahir's debut) are Rashid Khan, whose numbers are skewed by the opponents he has faced, and Kuldeep Yadav, still very early in his career.

Even besides all this, is his greatest service to legspin: to make it acceptable, even admirable, to be a white-ball champion and not obsess over how the red-ball figures look. In 2011 there was still a degree of old-school snobbery about this - that you couldn't be a proper legspinner if you hadn't done it with a red ball and in whites, or if you didn't break it enough or flight it enough. For a long while, Tahir assessments had a "but Adelaide" religiously appended. You're forever a product of your time, so it mattered to him too, enough for him to feel that he had "proved" he could play Test cricket when he did return.

It shouldn't have, not then and now it really doesn't. More than any other leggie before him, that is on Tahir.

***

In the way that there are days when watching Tahir is far more compelling than watching him bowl, the least interesting thing about Tahir's career sometimes was what he did on the field. His hair yes (clearly googly tips aren't the only thing Qadir passed on), but imagine that, as he leaves, we know so little about his being a Pakistani - a Lahori no less, so Pakistaniyat overload - playing for the team that is the least Pakistani team in all of cricket. Imagine how much could have gone wrong when you consider that the least difficult aspect of all this is how modern South African teams manage spinners - with all the panache of a seal handling a Rubik's Cube. How did this not end up in dysfunction, let alone work out as well as it has?

If this was England, where he also spent plenty of time, it would be easier to understand. Both the Pakistani experience and the Pakistani cricket experience are deep-set there. South Africa? If he had lived all his life there, then sure. But he was well into adulthood when he moved, and the modern Pakistani experience of that country is thin, centred around the flight of lots of the activists of the MQM - a bolshie, once-major, political party - in the '90s.

There are times when just watching Tahir is even more compelling than watching him bowl AFP

Love helped. He had the support of his wife. But we have, really, only a tiny idea from interviews, and not much beyond the platitudes you might expect. The fervour and vigour of his wicket-taking celebrations, those mad sprints to nowhere, and the kissing-stroke-assault of the Proteas crest, early on felt like little digs at Pakistan for not giving him their crest at senior level. But over time it has become clear how wrongheaded it is to think like that, because he was, after years and years of toil very obviously - and constantly - elated at being able to play international cricket at all, to be operating at the very pinnacle of his sport, for one of the sport's top teams. Also, by every account, there is not a malicious or bitter bone in his body.

There is, in fact, every chance it was as uncomplicated as this, that he was selected and thereafter given respect and treated fairly, and that South Africa needed a quality spinner. A professional equation that turned, quite organically, into a sense of gratitude, loyalty, duty, even love. All of it was evident in every ball he bowled, so much that it's impossible to think of him as a Pakistani bowler now. Even more in every piece of fielding - every time he ran at a ball, not circled it, or hit the stumps direct, or saved a run on the boundary with his throw. He isn't a natural athlete but he turned himself into a fielder South Africa didn't need to hide, in a way a Pakistani fielder would never have been in Pakistan.

On Saturday he will bring the drama one last time. The googly one last time, the Qadir-angled run-up one last time, the celebrations one last time. Likely he will finish his spell with a little look up to the sky, a prayer at the end, a kiss of the cap, hugs all around and some applause at the boundary he will be protecting. He will continue bringing it in T20 leagues around the globe, maybe even in T20Is for South Africa, but effectively, this is goodbye, Tahir bursting into that dying light, arms spread, chest out, Proteas crest prominent and proud.

Torrent Invites! Buy, Trade, Sell Or Find Free Invites, For EVERY Private Tracker! HDBits.org, BTN, PTP, MTV, Empornium, Orpheus, Bibliotik, RED, IPT, TL, PHD etc!

Results 1 to 1 of 1

-

07-05-2019 #1Be A Man Touch The Sky

- Reputation Points

- 431433

- Reputation Power

- 100

- Join Date

- Mar 2018

- Posts

- 24,214

- Time Online

- 246 d 9 h 20 m

- Avg. Time Online

- 2 h 40 m

- Mentioned

- 2351 Post(s)

- Quoted

- 452 Post(s)

- Liked

- 5104 times

- Feedbacks

- 521 (100%)

Why Imran Tahir is the daddy of modern white-ball legspin

Sweet Dream Nightmare Come Together

We are come from different Worlds

Who Will Really Care !!

Day Went Night Comes

Earth face this

untill the judgement day comes forever

People Here People There

Does Change The Clock

We Want To Be Damn Happy

Which Is Really the fact of this clock

= > NIL

How To Add Feedback Tutorial

TorrentInvites.org Forum Rules

How To Make Ratio Proof, Speedtest Proof or Seedbox Proof

LinkBack URL

LinkBack URL About LinkBacks

About LinkBacks

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote